Building with Tinker

Post Training Ensemble vs. Singular Model Approaches with Tinker

At Ramp, we like to experiment with new tech to see how it can make us faster. Last week, we got early access to Tinker from Thinking Machine Labs.

We wanted to see how Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) behaves when trained on datasets with different levels of diversity. Does training on a varied dataset improve transfer learning or does the added noise make learning less stable?

What is Tinker?

Tinker is Thinking Machine Labs’ platform built for efficient fine tuning and inference of open source models. The goal: bring these workflows together so you don’t have to juggle separate systems.

In practice, this means you can:

Host your model on Tinker

Send inference calls

Return rewards from those inferences

And update your model using the reward

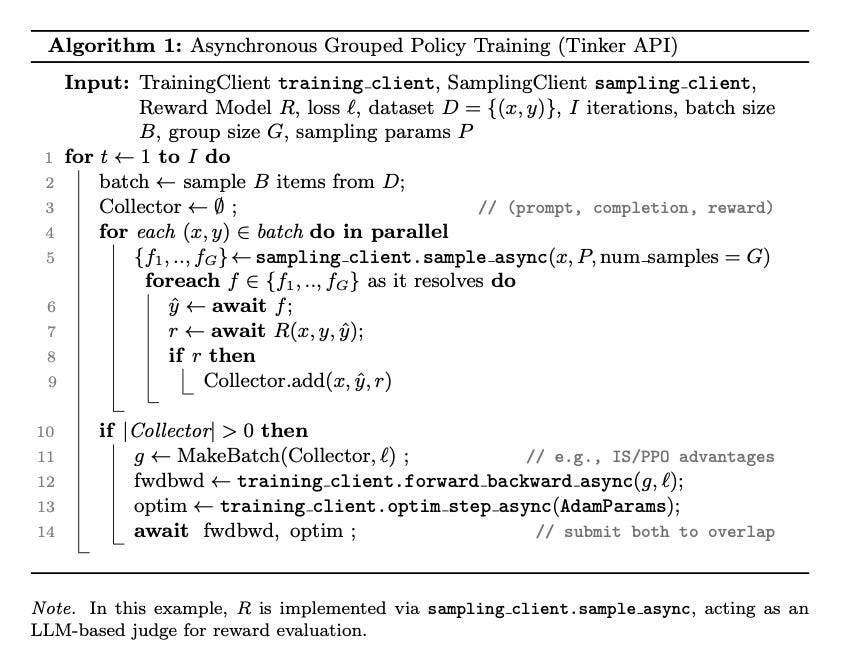

Tinker offers both synchronous and asynchronous APIs. By default you might use sync for simplicity, but for higher throughput you can switch to async. In our experiment we used the async functionality, streaming sampled outputs from Tinker to our reward function as they were generated, rather than waiting for full batches to complete. That allowed immediate feedback, quicker iterations, and higher efficiency.

One Caveat

Tinker doesn’t (yet) let you host custom reward functions unless your “reward” is another model. That’s fine until you try something like SpreadsheetBench, the reward logic was too heavy to run locally, so we had to host it remotely on Modal. It worked, but added lag and friction. We eventually switched to an LLM as a judge reward to simplify the setup and make it easier to see how Tinker actually performs.

The Setup

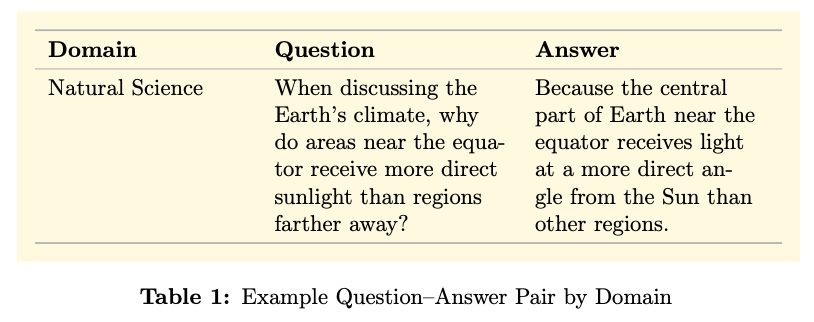

For the main experiment, we used the Salesforce Webscale-RL dataset.

2,500 Q&A pairs from each math, social sciences, and natural sciences were selected.

2,000 for training, 250 for validation and test sets each.

We trained three domain specific models (Math, Social Science, and Natural Science) and a multi domain model trained on the combined data from all three single domain runs. Every experiment used the same hyperparameters, batch size, and group size to keep comparisons fair. The policy model we fine tuned in all four cases was Qwen-8B with LoRA rank 128.

Because the multi domain model was trained on all three datasets together, we gave it three times as many training iterations while keeping the batch size fixed. This ensured it saw the same data as the individual models combined. We used importance sampling with normalized group advantages to keep gradient updates stable across batches.

For evaluation, we used Qwen3-30B-A3B-Instruct-2507 as an LLM as a judge. It compared each model’s output to the reference answer and assigned a binary reward.

Training

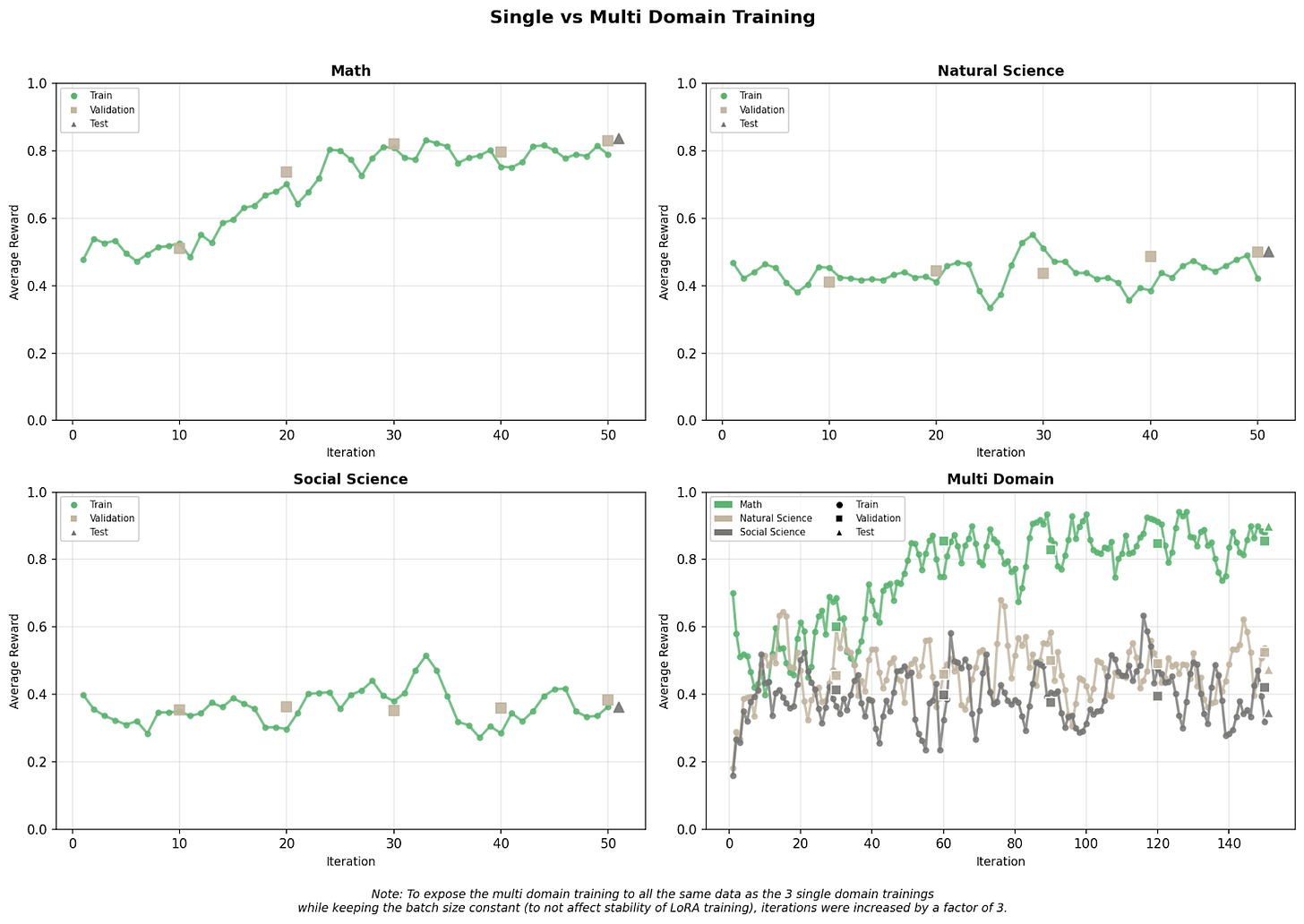

The math specific model showed the fastest and most stable learning. Its reward curve settled quickly, which makes sense given how structured and well defined math reasoning tends to be.

Models trained on social and natural sciences were less steady, with noisier gradients and slower convergence. That probably comes down to their dependence on external knowledge, it’s harder to learn clean patterns when the task itself is full of context and ambiguity.

The multi domain model introduced volatility. Its training trajectory was less stable and often spiky, particularly early in learning. Yet this volatility wasn’t purely harmful: the multi domain model slightly outperformed the math only model on math evaluation. This suggests that exposure to varied reasoning forms (e.g., causal inference or narrative reasoning) may have helped the model develop more generalizable heuristics. Regularization effects likely also contributed, as multi domain exposure reduces overfitting to any single reasoning style.

Head to Head Comparison

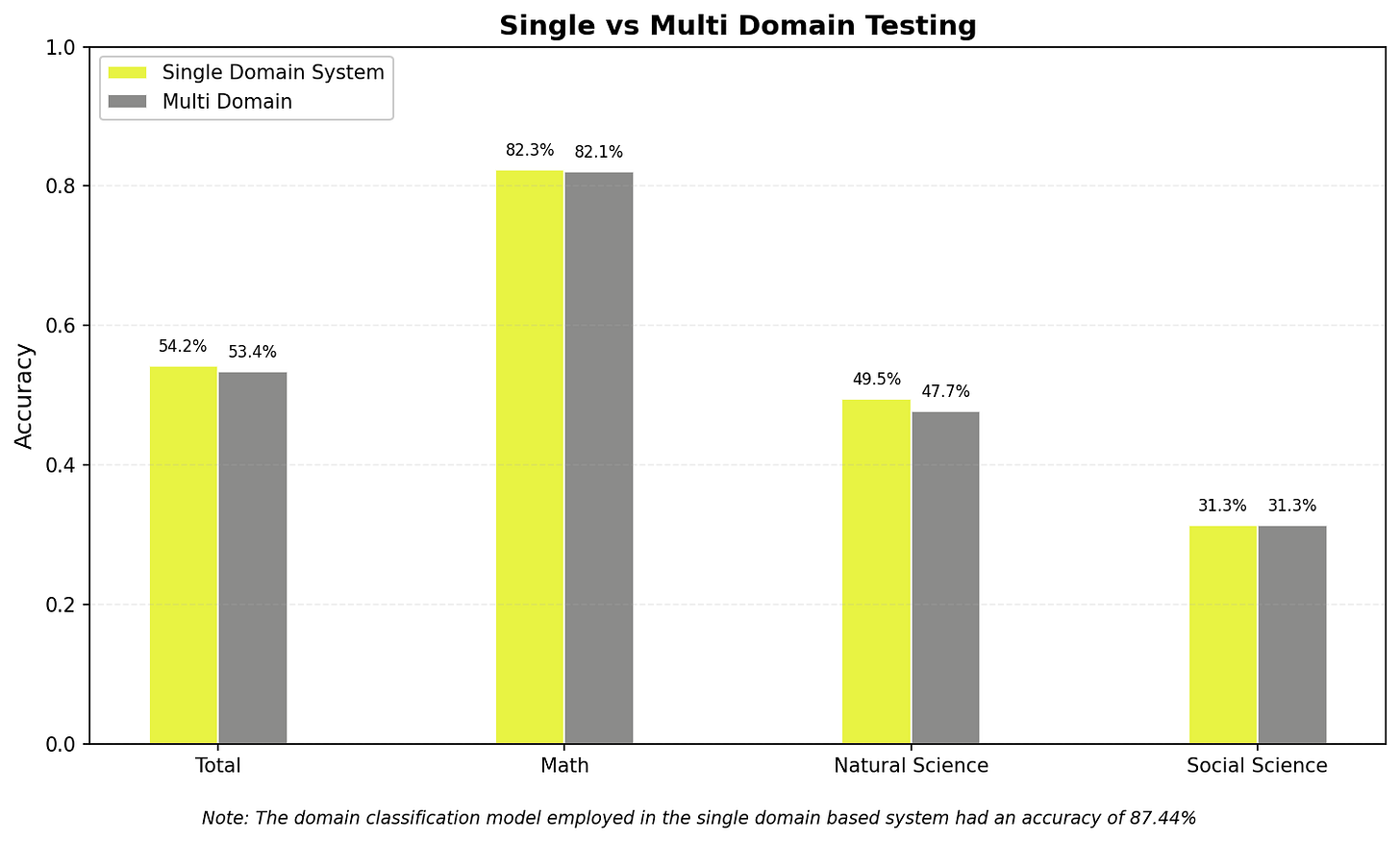

To see how the models stacked up, we tested everything on a shared test set: the combined test data from all three single domain runs. Since we wouldn’t know a question’s domain in a real setting, we used an untrained Qwen3-4B-Instruct-2507 to predict the domain and route each question to the corresponding single domain model—functionally similar to an MoE system. The multi domain model just answered everything directly. For evaluation, we used each model’s best validation checkpoint and relied on Qwen3-30B-A3B-Instruct-2507 as an LLM as a judge to generate consistent binary rewards across runs.

Performance was roughly equivalent across systems. The domain classifier’s imperfect accuracy likely degraded the single domain system slightly, but not by much. The main difference was efficiency: the multi domain model took about three times longer to train.

Conclusion

From these experiments, one clear takeaway stands out: segmenting training by domain and running processes in parallel can make post training far more efficient. The single multi domain model didn’t deliver enough benefit from transfer learning to justify its heavy runtime and its learning was less stable overall. For large scale post training, this domain split approach could deliver substantial wall clock savings without sacrificing performance.

So what do we think of Tinker? The system made it remarkably easy to run inference and update models without getting lost in infrastructure work. It let us focus on the research instead of the plumbing. That said, native support for remote reward functions would be a real breakthrough, enabling heavier computational experiments without clunky workarounds. Overall, Tinker feels like a thoughtfully built platform that lowers the barrier to RL research making complex post training workflows accessible to individual researchers and smaller teams alike.

Want to keep up with our next AI experiments? Subscribe here and follow us on @RampLabs. We’re also hiring across roles at Ramp.

Great article!

So cool!